How Special Economic Zones Kickstarted the Chinese Economy (Part I)

Liberalization with Chinese characteristics

Initially, this was to be a single post, but as I did more research and pushed back my deadlines I realized I could not do this topic justice while maintaining a reasonable length, so the post has been divided into two parts.

Following the fall of Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng and the rise of Deng Xiaoping as paramount leader of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a period of opening up to international markets and foreign capital began to take root. This would become one of the most significant economic stories of the post-war era—the rise of China as a global economic powerhouse.

These achievements were made possible, in large part, by China's approach to gradual institutional experimentation, epitomized by its Special Economic Zones. China’s experimentation began in earnest with the inception of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in 1980. These zones—geographically delimited areas managed by dedicated authorities, where business rules and incentives differ from the rest of the country—were designed to attract investment and foster rapid development (Ge 1999; Hamada 1974). Shenzhen, initially a small fishing village with a population of roughly 20,000 in 1978, would transform into a major technological hub serving a population of over 20 million residents with an output of hundreds of billions of dollars per year by 2018.1

To get a feel for the scale at which Shenzhen alone has ascended to, export volume grew from a measly $9 million in 1979 to a staggering $244 billion in 2017—an average annual growth rate of 27.3 percent. By 2018, Shenzhen had eclipsed regional giants like Hong Kong at a GDP of 2.42 trillion yuan—growing at an average annual rate of 22.4 percent. The residents of Shenzhen benefited massively from this growth miracle—disposable income per capita grew from 1,915 yuan in 1985 to 52,938 yuan in 2017, or a 26.6-fold rise in disposable income.

Now, this growth is impressive by any measure, but is there genuine structural transformation? From 1983 to 2017, Shenzhen produced 381,230 times more microcomputer equipment and 4,260 times more integrated circuits—an encouraging sign an economy is venturing into high value-added production. Shenzhen is home to some of China’s (world famous) national champions, like Huawei and Tencent, which are rapidly propelling China to the technological frontier.

Local firms based in the Shenzhen SEZ were able to cut their teeth by competing with international companies and had opportunities to learn from them by establishing joint ventures or other partnerships. The growth of Shenzhen-based industries spurred their expansion into neighboring regions and catalyzed their development. Millions of Chinese migrated to the Shenzhen SEZ in search of employment and new opportunities. Many found these opportunities and sent portions of their income back to their families, functionally subsidizing demand and spurring further development. The success of the Shenzhen SEZ, its counterparts, and spillover effects are credited with solidifying China’s (controlled) transition to a market economy and catalyzing the country’s economic development.

Today, there are thousands of SEZs scattered across China, with a diverse set of incentives to develop specific industries and spur regional development. As China becomes an upper-middle income country, its SEZs begin to lose their significance as the once endless waves of cheap labor from the countryside begin to subside, productivity rises, and firms and workers climb the global value chain. To avoid stagnation, China must become a world-leading innovator; the foundation of which has been firmly planted by its special economic zones.

A necessary condition for SEZ success is a strong institutional foundation, without which the SEZs will almost certainly fail. SEZs are burdened with major costs like providing infrastructure, land, subsidized utilities and lines of credit at favorable rates, but limited revenue from low-tax incentives makes financial sustainability challenging (ABD, 2015, p. 92). The Asian Development Bank (2015, 92-93) emphasizes these institutional arrangements are essential to manage these financial pressures and coordinate complex operations. SEZs must operate with a stable and unambiguous legal framework—i.e., predictability and minimal confusion. The authority governing the SEZ must be able to meet the needs of investors across a wide range of activities—such as land use and zoning, taxation, customs, labor, etc. Finally, property rights must be secure for foreign capital to flow—otherwise, investment risks may be too high. These conditions must all be met for success to be possible.

For underdeveloped economies seeking to catalyze development, SEZs are a practical tool to experiment with institutional design. They give governments the space to test various institutional arrangements to connect with international markets in a gradual and managed way, while preserving national institutions that may protect firms that are not yet fit for foreign competition.2 SEZs can be essential tools for regional development, particularly when countries face constraints like weak national institutions or limited linkages across the broader economy (ABD, 2015, p. 88).

A Crash Course in China’s Economic Development

China’s experimentation with SEZs demonstrates that wholesale liberalization need not be pursued to further economic development. Liberalizing pockets of the domestic economy allowed China to reduce adjustment costs and avoid some of the pitfalls of rapid liberalization—primarily premature deindustrialization like that experienced in other Asian countries and Latin America (Furusawa and Lai, 1999; Rodrik, 2016). The gradual approach to market reforms is described in China as “crossing the river by feeling the stones”. This proverb captures the essence of China’s cautious experimentation with marketization.

As mentioned, China began its reform process in 1979-1980 with the creation of the Shenzhen SEZ, along with the Shantou, Zhuhai, and Xiamen SEZs. China’s economy was just emerging from the cultural revolution orchestrated by Mao and the Gang of Four—targeting academics, scientists, intellectuals, and any other “remnants” of capitalist class and Chinese tradition. While not as economically disruptive as the Great Leap Forward, many prominent leaders were exiled to the country-side, including Deng Xiaoping and Xi Zhongxun.3 The loss of experienced and pragmatic leaders was a serious blow to the PRC and former leaders only made their permanent return to influence following Mao’s death in 1976 (Naughton, 2018).

With Deng’s return to power, economic rationalization finally entered the economic policy of the PRC.4 It was clear to Deng that reform was needed but he did not have unilateral authority to pursue it—he needed the support of the conservative old guard.5 By pursuing reform within geographical testbeds, Deng was able to hold back the conservative wing of the party by demonstrating that he did not intend to loosen the party’s grip on power by allowing foreign capital to dominate the Chinese economy. Furthermore, some reformists (those that ultimately triumphed) feared the relaxation of price controls in one “big bang” would unleash an inflationary spiral that would lead to instability and the loss of their grip on power (Weber, 2021, p. 11).6

While on a visit to Ireland (among other countries) Chinese officials discovered their inspiration for the special economic zones—the Shannon Free Zone. The Shannon Free Zone was established to revitalize an area that was dependent on refueling trans-Atlantic flights until these flights had the range to bypass Shannon altogether. The free trade zone offered tax holidays, low corporate tax rates, tariffs were slashed or eliminated, companies received value-added tax exemptions—all contributing to Shannon’s survival and revitalization.7

China took this model and began to apply it to select coastal cities (as noted above)—easily accessible and prime locations for urban development. China’s SEZs operated much like the Shannon Free Zone and other SEZs of the day. Foreign investment was encouraged via a favorable low-tax environment, imports of components and supplies were duty-free, and tax holidays, when given, lasted from 3-10 years. The SEZs streamlined administrative procedures and acted as a one-stop-shop for permits and regulatory exemptions. The zones also had the authority to pursue infrastructure projects and supply utilities to foreign firms (ADB, 2015, p. 92-93; Naughton, 2018, p. 665).

Unlike other SEZs, China’s SEZs, as we have established, experimented with domestic policies as they were granted a high degree of autonomy. The Shenzhen SEZ implemented the country’s first flexible wage system but later legislated the country’s first minimum wage. The SEZs also experimented with land markets and were designed as laboratories to absorb knowledge to advance technology, administration, and business (Naughton, 2018, p. 666).

These zones—as you have likely noticed—are specifically designed to benefit firms and foreign capital, while wages are suppressed to minimize labor costs. This is typically how capitalist development proceeds. There is a surplus of labor in the agricultural sector that contributes little to the sector’s output—i.e., the marginal product of labor is near zero. Once a small manufacturing sector (or capitalist sector to be more general) is established, the marginally higher wages will attract the unproductive surplus labor of the country-side—raising the productivity of the agricultural sector by reallocating its surplus labor to manufacturing, which produces things workers need and agricultural machinery. Further raising agricultural productivity and making the marginal farmer redundant in a self-reinforcing process (Lewis, 1954).

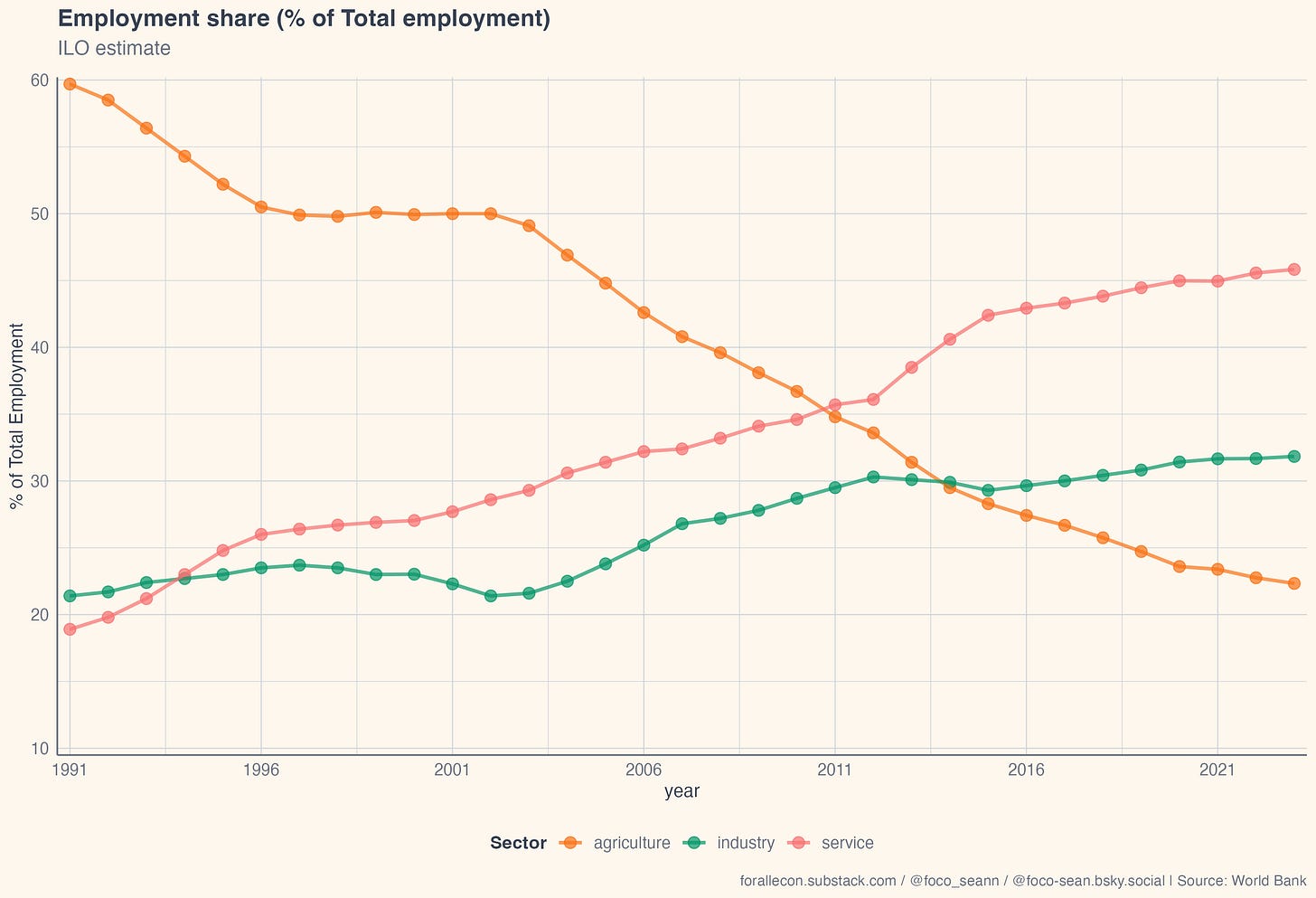

This is precisely the process that occurred in China: from 2005 to 2010 more than 10 million people migrated to the cities per year and the share of employment in agriculture experienced a secular decline while manufacturing rose (Naughton, 2018, p. 266). The reallocation of labor to higher value-added industries is likely to have been accelerated and potentially caused by China’s gradual integration into the global economy via the implementation of SEZs and its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO).8 The gradual introduction of market incentives allowed Chinese firms to acquire foreign capital and eliminate the most inefficient firms on the margin while reducing adjustment costs that would otherwise result in potentially millions of workers losing their employment—that said, there would likely still be a net gain in manufacturing employment had China not taken the gradualist approach.

What are the mechanisms by which China’s development may have occurred? Agglomeration economics gives us a solid foundation to understand how China’s SEZs kickstarted its rapid development.

Agglomeration Economies

This theoretical framework allows us to understand why economic activity clusters in geographical areas through a variety of incentives—this should sound familiar. Agglomeration economies are defined by three characteristics: (1) infrastructure sharing, (2) labor pooling and matching, and (3) knowledge spillovers. There are two types of agglomeration economies: localization economies and urbanization economies. The former refers to the cost savings for firms that locate near other firms of the same industry. The latter is defined as the cost savings for firms located near other firms of different industries.9

The phenomenon of agglomeration is most readily associated with economies of scale—the fall in costs as output expands, which results in the decline of costs per unit of output (Bolter and Robey, 2020).10 For instance, average travel costs ($/user) for the Minneapolis Metro Transit will fall as the number of users grows. Each movement from one station to the next will have relatively similar total costs, but as ridership grows the system becomes more financially viable, encouraging the expansion of the system in a self-reinforcing manner; this will be balanced by costs induced by congestion. This line of thinking can be applied to other utilities like energy and telecommunications.

Firms also need workers (and vice versa) and where there are jobs there will be workers (as evidenced by the rural-urban migration in China). Suppose this workforce becomes more educated over time, then more advanced manufacturing and service oriented firms will establish themselves in the area. This will then attract more educated workers as they understand that their labor will be in demand (Bolter and Robey, 2020). In addition, thick labor markets will reduce spells of unemployment and improve skill matching between employer and employee.11

Finally, infrastructure sharing, labor pooling and skill matching reduce the cost of generating new ideas by facilitating their exchange between workers and employers, leading to knowledge spillovers. The close proximity of firms and workers allows for the exchange of knowledge, which can lead to a rise in innovation and productivity. In areas that are more skill dense, workers are able to learn from one another more quickly. By investing firms can accelerate the pace of technical change as they understand that skilled workers will be present in the labor market. At the same time, workers know their skills will be in demand so they will invest in human capital (Bolter and Robey, 2020).

Applying Agglomeration to China

The establishment of SEZs has directly facilitated the growth of agglomeration economies—beginning on China’s eastern coast, then slowly moving inward toward its interior. The experimental institutions adopted in the SEZs have attracted numerous firms, while drawing labor out from the country-side to the coast in search of new opportunities. This combination has created a favorable environment for firms by pooling labor into a limited geographical area and by improving the financial viability of urban infrastructure—producing a self-reinforcing cycle of labor market thickening balanced by congestion.

Workers begin to learn from one another, while the SEZ subsidizes education for their children—continuously upgrading the skills of the workforce and drawing in firms higher on the global value chain (Khandelwal and Teachout, 2016). However, much of the circular causation rests on the assumption that SEZs can keep up with infrastructure investments or do not have political opposition to its expansion. China’s passenger rail network may be an attempt to propagate agglomeration by reducing transportation costs to facilitate the exchange of ideas and people from one region (SEZ or not) to another (Chatman and Nolan, 2011; Yao and Luo, 2024).

China has clearly constructed a dense and wide network of passenger rail lines across the country, focused primarily on its coasts and east-most interior to allow for convenient and fast transportation. This network maps nicely onto China’s major population centers, fulfilling a necessary condition to maximize the gains from agglomeration economies. In contrast, the United States has a sparse passenger rail network and has not invested in its construction on a similar scale to China—that said, the US is an advanced economy, so infrastructure investments will systematically be lower. Only the Northeast Corridor offers “high-speed” rail (HSR), but this tops out at 240 km/h (150 mph) on limited segments (~800 km). China, on the other hand, has a vast network of HSR stretching 25,000 km in 2017—almost double this count in 2024—and reaches speeds of 350 km/h (217 mph).

Laying the foundational shared infrastructure encourages further investment and can catalyze agglomeration.12 However, it is likely China has reached a severely diminished return on capital investments, given its dual strategy of investment-led growth. The following plot reveals that China’s investment as a share of GDP remains stubbornly high compared to a developed consumer market like the United States, which is a product of China’s “forced” savings and capital controls.

Juxtaposing China’s macro-imbalances and its massive passenger rail network with that of the United States is revealing. China bet big on HSR to drive agglomeration, sometimes beyond what financial returns justify (Mao et al. 2022). The US made the opposite bet—minimal HSR investment despite clear agglomeration opportunities (Chatman and Nolan, 2011).

The agglomeration framework helps explain why geographically delimited areas—SEZs—may grow and develop more rapidly than other regions—infrastructure and transportation costs fall, ideas spread, firms and workers concentrate, workers pursue education, and productivity rises. This occurs in a self-reinforcing cycle that is balanced by rising congestion costs. In Part II, I will explore the empirical literature and discuss the variety of economic outcomes SEZs produce, the institutional features that drive this variation, and whether they are effective tools to catalyze economic development.

Much of the statistics of this section are taken from Johnson and Davis (2019), a UN Habitat report.

However, protectionist lock-in is a very real threat to efficiency and, in some cases, can only be broken in the most extraordinary of circumstances (Lane, 2024). Commitment to SEZ implementation may minimize this threat, otherwise there would be more barriers to trade and capital.

The latter being President Xi Jinping’s father.

That is, the pursuit of efficiency and minimization of costs by introducing market forces.

“Conservative” as in they support the planned economy.

Weber makes this case throughout the book.

It must be understood that Ireland, around 1956, was in an autarkic state and vastly poorer than its Western European counterparts. Today, this is not the case.

It is extraordinarily difficult to conclude China would not have developed in this manner had they not taken this policy path, but there is evidence to suggest this is the case. I must stress here that causality is extraordinarily difficult to establish empirically.

To keep your attention I will not dive into the details.

Bolter and Robey (2020) is a literature review of agglomeration economies.

A thick labor markets is one in which there are many buyers (employers) and sellers (workers).

However, there is potential for investment to be locked-in to high-investment regions (agglomerated), creating a center-periphery dynamic where low-investment areas are plagued by low growth (Fujita, Krugman & Venables, 2001, p. 79-95). A benevolent social planner would be able to direct investment to the periphery to eliminate this bifurcation (China does in fact build trains to nowhere and other investment may eventually follow, but there are enormous costs to construct high-speed rail and much of the network does not break even).